The Psychology of Social Engineering

Why People Fall for Scams and What Your Company Can Do to Intervene

We’ve all felt it – the flash of gut-wrenching panic when you get a text or an email from some authoritative entity like the IRS saying you’ve done something wrong and owe money immediately to sort it out.

In one scenario, you take a second and re-read the message. “Why would the IRS text me?” you wonder. And upon closer examination, you might notice the URL isn’t official looking, or that words are misspelled. Finally you realize it’s a scam, and you hit “delete and report junk”, quickly moving on from what originally had you feeling quite concerned.

However, in another scenario, you think, “Oh no, I need to do something about this issue!” and you click the link without thinking, and quickly fill out your banking information, believing you’re now cooperating with the IRS.

Maybe you realize it’s a scam right after you’ve submitted your personal information when you’ve had a chance to consider the initial message. Maybe you realize it a few days later when you see the first suspicious charge on your account.

In the latter scenario, you’ve done exactly what the scammers wanted: You followed your emotions and played right into the psychology of social engineering scams.

If You Have Emotions, You Can be a Victim of Social Engineering

No one is immune to a scam. You may think you’re smart enough to spot one, but the reason social engineering scams are so successful is because they prey on human weaknesses that everyone shares.

Scammers use the same psychological manipulation techniques as the CIA and governments around the world to tap into human emotions.

There are numerous social engineering tactics bad actors use to scam us:

Phishing: Fraudulent emails or other messages that deceive people into installing malware or revealing personal information, such as passwords or credit card numbers.

Vishing: Fraudulent phone calls or voice messages that pretend to be from a reputable company in order to deceive people into revealing personal information, such as bank details and credit card numbers.

Smishing: Fraudulent text messages that pretend to be from reputable companies or individuals in order to deceive people into revealing personal information, such as passwords, bank account numbers, or credit card numbers.

Spear Phishing is another scammer tactic that targets a specific person or group with information that interests them, like financial documents or current events, in an effort to gain access to personal information; Whaling is a scammer tactic that targets high-profile individuals like CEOs or CFOs; and Angler Phishing is a relatively new scammer tactic that targets individuals on social media by posing as a customer service agent trying to help a disgruntled customer in an effort to obtain personal information or account credentials.

With so many tactics, it’s no wonder the success rate of these social engineering scams is so high; Security Magazine reports between 80-90% of cyberattacks begin with social engineering scams, and more than 90% of businesses reported experiencing a phishing attack in 2024.

PROTECT YOUR ORGANIZATION AGAINST RISING VULNERABILITIES

Scammers know how to tap into some of our most basic emotions to get what they want.

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) – These scams will alert you to a package that cannot be delivered due to missing information, or inform you of winnings or a prize you need to claim within a certain amount of time before you lose the chance.

Example: “Congratulations! You’ve been selected to receive a free iPhone 15. Claim your prize now before it’s gone!”

Anxiety – These scams will typically reference a service or benefit you need and inform you of an issue or problem that needs to be fixed with an immediate payment or clarification of your information.

Example: “Your health insurance has been suspended due to an issue with your latest payment. Reactivate now to avoid loss of coverage.”

Fear – These scams will tell you that your information has been compromised and will ask you for immediate action to prove your identity and secure your assets.

Example: “Your bank account has been accessed from an unauthorized location. If this wasn’t you, click here to secure your account immediately.”

False Sense of Urgency – These scams create an urgent situation related to something important in your life (money or access to information) that needs your immediate attention.

Example: “Your email storage is full, and your account will be deleted in 24 hours. Click here to upgrade now!”

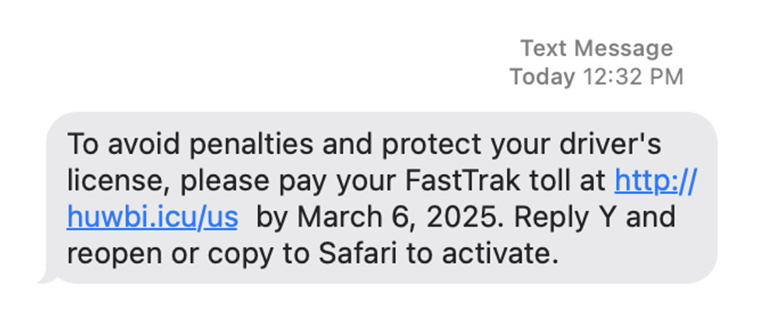

In fact, while I was writing this piece I received the following text message:

This message is a perfect example of a smishing scam that plays on anxiety. But right away you can tell the URL doesn’t look official to FastTrak, and the directions to reopen or copy the URL to Safari to activate are not typical of a business correspondence.

Furthermore, and perhaps most tellingly, I do not have an account with FastTrak – I use another toll collection system. But scammers are hoping you’ll be so anxious to get this issue taken care of that you won’t read between the lines or register the obvious inconsistencies.

We don’t always think about social engineering scams as being emotional, when in fact they are nothing more than emotional manipulation. At the root of all scams is the blind trust in institutions and authority we form at young ages, so when an email comes through claiming to be from one of those entities, like the IRS, it’s easier to get caught up.

This blind trust means organizations need to do extra work to educate their employees to be more skeptical before responding to an email or text message.

Stay Updated with Cybersecurity Insights

Training Employees to be Aware of Social Engineering

We talk a lot about the importance of educating and training employees about how they can strengthen corporate cybersecurity – selecting complex passwords, logging out of their accounts when not at their desks, and being aware of social engineering scams.

I advocate for employee education and training, but there is an important followup – it needs to be put into action. If employees aren’t tested regularly on what they know, they’ll forget. People get busy and the rules of social engineering awareness can go right out the window.

Here are a few ways to keep social engineering education and training top-of-mind:

- Run fake phishing campaigns. Send out phishing emails to employees and monitor who takes the bait.

- Test identity validation. Call employees pretending to be a specific employee asking to change an account password and monitor who asks for a second form of identity validation, such as a video call or MFA.

- Focus on emotions. When conducting education and training, discuss the emotional manipulation inherent in social engineering scams so employees understand what it is and how to recognize it.

If you can pair training with execution, you’ll see which social engineering tactics your employees fall for more often and you can identify reoffending individuals for more targeted training.

If you can pair training with execution, you’ll see which social engineering tactics your employees fall for more often and you can identify reoffending individuals for more targeted training.

There will likely be a weak point somewhere in your organization, which is why social engineering is one of the most-used attack vectors. Attackers can easily get into some of the most secure places with no credentials just from a simple correspondence.

DirectDefense offers social engineering campaigns as part of penetration testing. In my role in the SOC, we’re on the blue team side seeing those attempts and trying to catch them on behalf of the customer.

What we do in the SOC is manage the abnormal events, and we offer a service called Supplier Payment Change Request where we validate payment change requests from customers on behalf of our clients. While it is perfectly normal for a company to change suppliers and request funds be rerouted to another bank or supplier payment system, those requests are all-too-common for social engineering scams.

Attackers prey on what’s personal to us, and getting around the initial emotional reaction to a social engineering scam requires training and continued execution to ensure employees are always looking twice at something that seems even mildly suspicious.